The end of the summer can be a stressful time for many scientists. Professors, researchers, and graduate students, returning from busy months of presenting their work at conferences, writing journal papers, and catching up on research, must now prepare for the return of university students and the coming school year. If you can remember the dread of going back to school after the summer holidays, you probably don’t find it surprising then that many of us end up looking for distraction on social media.

In the first week of August, a procrastinating biologist on Twitter decided to paint his study subject in Microsoft Paint and tweeted it, along with a call for others to do the same under the tag #MSPaintYourScience. The scientific corner of the “Twitter-sphere” was immediately delighted, and hundreds of child-like drawings of animals, environmental processes, geology, and more poured forth. As a distracted graduate student myself, I couldn’t help but get in on the fun (and nostalgia) of using MS Paint to do a somewhat wobbly laptop trackpad portrait of the telescope I use for my science, the Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico.

As a relatively new Twitter user, I was surprised at how popular the tweet became and how much positive feedback I got, along with questions about my science. Given that scientists often have reputations as being too-serious, #MSPaintYourScience was a great way to show that we can be playful or artistic about our often obscure-seeming work. Radio astronomy, in particular, can be tough to explain, so using many different mediums to catch public interest and tell people about it is very important. Luckily for us astronomers though, we have lots of beautiful images and art-inspiring subjects to show people how amazing the universe can be.

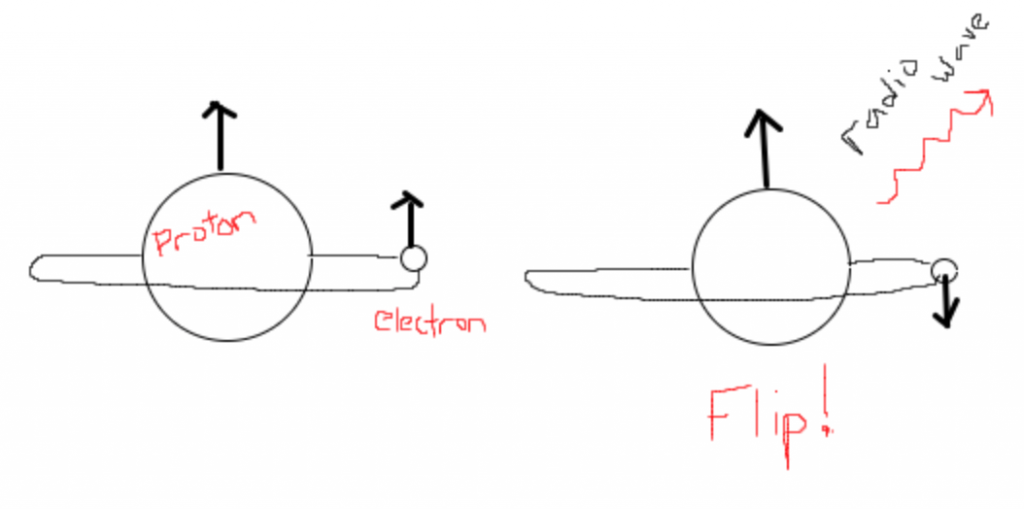

My work, in particular, uses the VLA to study hydrogen in and around galaxies out to large distances. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, so we can see signs of it everywhere from our own galaxy to the most distant reaches of the universe. It is the fundamental building block for star formation, so understanding how galaxies acquire their hydrogen fuel to build new stars is a crucial question to answer if we want to understand how galaxies grow and evolve. The VLA is a radio telescope, and thus the perfect tool to study this, thanks to a unique property of hydrogen–a quantum mechanical effect that causes it to emit radio waves!

Because we want to understand how galaxies grow over time, we make use of the fact that in space, looking farther away is equivalent to looking back in time due to the finite speed of light. Thanks to an upgrade a few years ago, the VLA can now look back farther than ever before. To make use of this, the team I am a member of designed our project, which we call CHILES (the COSMOS HI Large Extragalactic Survey).

CHILES is looking at a single patch of the sky about the size of the full moon in the COSMOS field, a part of the sky that is well-studied by other telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope. However, to collect the faint radio emission from the most distant galaxies the VLA can see, we need to observe for a long time. CHILES is, therefore, collecting 1000 hours of data!

With this huge amount of data, we hope to understand how hydrogen is distributed and moves around distant galaxies, whether the total amount of hydrogen has changed over time, and how different environments might affect a galaxy’s hydrogen content (and thus star formation). All of these questions move us closer to understanding how our own galaxy formed, and thus how the conditions for our existence arose.