“Music is the one incorporeal entrance into the higher world of knowledge which comprehends mankind but which mankind cannot comprehend.” Ludwig van Beethoven

“Music doesn’t lie.” — Jimi Hendrix

They get me every time… new images from space. Whether it’s a Hubble picture of glowing bits of stellar fluff in our own little corner of the universe or ALMA unveiling a pair of distant galaxies ripping each other to shreds, the cosmos provides a never-ending feast for the eyes. And even after a few decades of science outreach and seeing some of the best that astronomy has to offer, I still have those “wow!” moments. Today, however, was different. Today, that “wow!” moment wasn’t visual, it was sound: a dataset that had been converted into a haunting concerto.

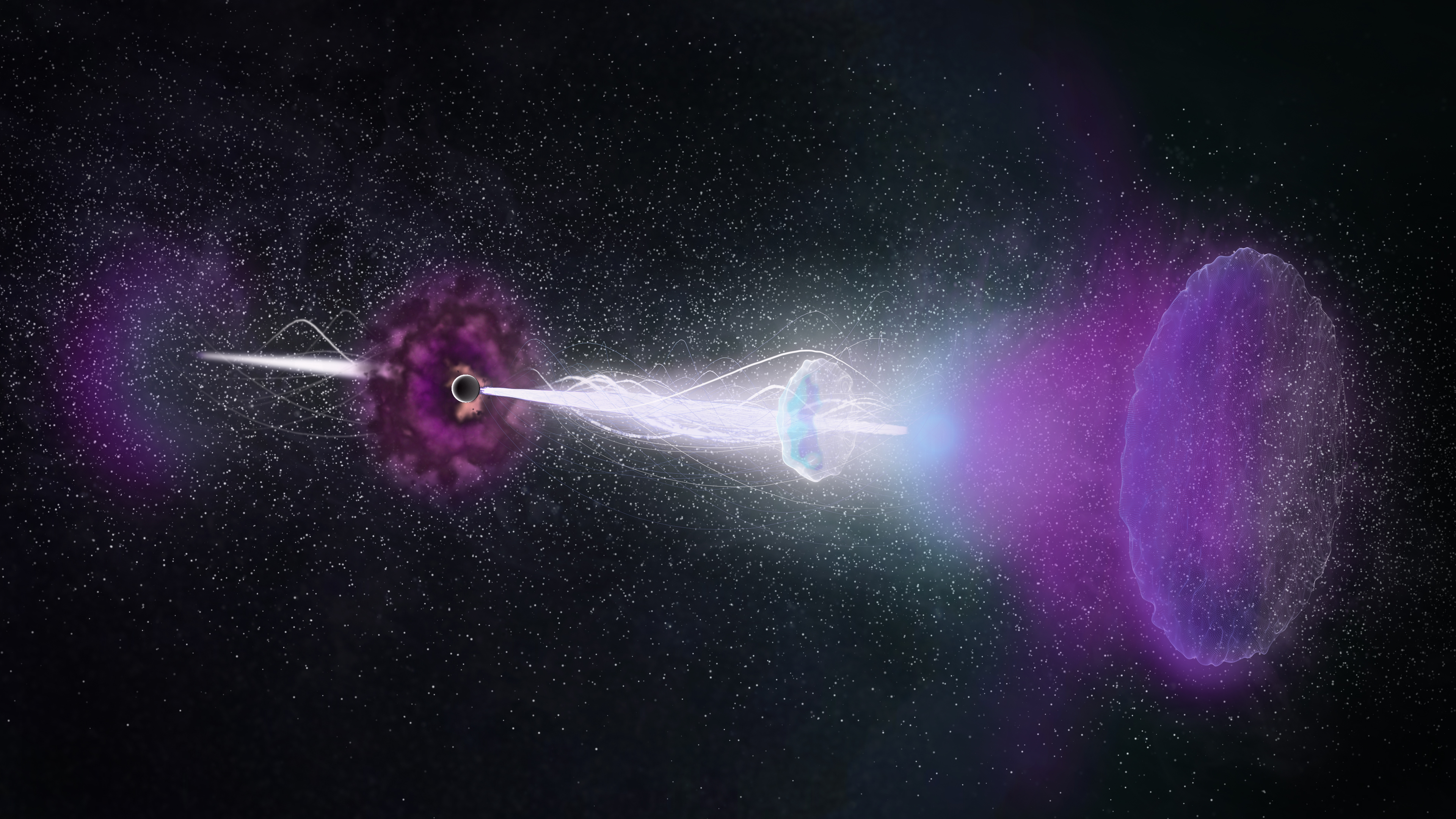

This cosmic music came from a team of astronomers observing a gamma-ray burst – a whopping stellar explosion that blasts beams of ultrahigh energy gamma rays right at Earth (though at 2 billion light-years distance, it went mostly unnoticed except for a few intrepid bands of plucky astrophysicists).

The full release – which you can read here: https://public.nrao.edu/news/2018-alma-cosmic-explosion/ tells the story of ALMA’s first-ever time-lapse movie of a stellar explosion. It’s a gripping tale of power, resistance, and the enduring glow that scientists thought would be little more than a fleeting flash. The lead astronomer on the project, Tanmoy Laskar, wondered, however, if there was something more intrinsically interesting in the rise and fall of the millimeter-wavelength light shown in the data. There was something almost melodic in the way the data seemed to appear on his graphs and charts. So, why not take that data and convert it to sound? The result… a tune worthy of a Grammy, if there were a category for astrophysics.

Converting data to sound is not a new idea. When the National Science Foundation announced the first detection of a gravitational wave with LIGO, they played a rather spritely “blip” to highlight the discovery (the data had to be stretched out and amplified a GARGANTUAN amount before being converted to sound, but the effect was nice).

This idea of presenting otherwise silent data as an auditory treat is called sonification; it’s simply taking information about light, mathematics, rainfall, traffic patterns — anything really – and assigning a sound or note to the various bits and bytes that would otherwise appear as humdrum numbers on a page. But take those numbers, add pitch, voice, tempo and suddenly the information – in a sense – leaps off the pages. Laskar (also a composer and musician) did something similar with the help of chemical engineer and electronic music artist Melike Yersiz.* In this case, though, it wasn’t a single “blip” on a graph… it was an enduring rise and fall that played out over many weeks. Scrunching it down to 53 seconds while applying a consistent sound scheme and you get, what could be called, the Music of the Exploding Sphere**:

To be clear, sound does NOT travel through the vacuum of space. And addressing a common confusion, radio astronomers are not “listening” for anything. But sometimes the data have more to tell us than just our eyes can perceive. Human ears and the auditory centers of the brain are amazingly powerful data-analysis tools. The most subtle shift in tempo, pitch, harmony and key can stand out like a sore thumb, even when the raw data appear rather ordinary at first glance.

This innate musical talent we all have can give astronomers (and us) a fresh way to appreciate a discovery or observation and – perhaps – learn something we couldn’t readily discern by just looking at the data or seeing an image – no matter how gripping or evocative.

“While we may be familiar with using graphs to represent numbers, the use of sound for data visualization is less common. Sonification, or turning data into non-speech sounds, provides a non-conventional, different representation of data. As the process of generating and perceiving sound intrinsically has a time dimension, it lends itself extremely well to time-series data, i.e. data with an inherent time order. In the study of astrophysical transients — measuring the brightness as a function of time is the primary means of learning about the source. Sonification preserves the temporal relation between events, and thus may provide an interesting approach to identifying correlations in astronomical observations.” – Tanmoy Laskar, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley, and a Jansky Postdoctoral Fellow of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

If you are intrigued by the mixing of art, music, and astronomy, there are a few other examples and a lovely explanation of how ALMA data were converted to basic sounds and then made into genuine music. See [www.almasounds.org]

** You can experience more of Laskar’s music at scholar.harvard.edu/laskar/music and Yersiz’s works at http://www.melikeyersiz.com/music

** The music of the spheres – or harmony of the spheres – is an ancient Greek concept that celestial bodies make music.