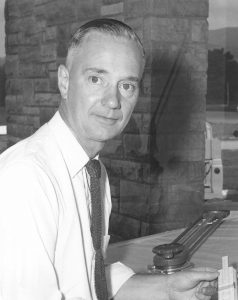

A radio astronomy pioneer, Grote Reber was inspired by Karl Jansky’s discovery of radio waves coming from the center of our Galaxy in the 1930s. Reber was only in his twenties when he built a 31-foot dish antenna in his backyard in Wheaton, Illinois. With it, he mapped the sky in radio waves, giving more detail to Jansky’s detections, while also discovering more radio sources in space. Reber moved to Hawaii and later Tasmania to build antennas to pick up the hard-to-detect long wavelength radio waves coming from the Universe. He died in 2002.

ALMA in its Compact Formation

ALMA’s antennas can be rearranged to simulate a single, big telescope or a very widespread array. In this smaller configuration, 12-meter antennas join the 7-meter antennas that are always in a compact formation. ALMA, when it is in its compact formation, sees the faintest objects in the radio Universe.

Atacama Compact Array

The heart of ALMA is the Atacama Compact Array. These smaller 7-meter dish telescopes, flanked by a few larger 12-meters, are practically touching each other to simulate a single telescope. When their views of the sky are combined, they can see the very faint radio-wave objects in space.

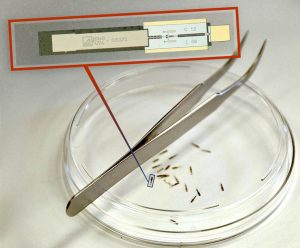

Band 6 SIS Mixer

The largest millimeter array in the world relies on the tiniest electronic parts. These are mixers for the receivers used in all ALMA antennas. Their job is to convert the cosmic radio source into an electrical current and then combine, as quietly as possible, the signals from the array’s metronome, called the local oscillator, with the signals the antenna receives from space. This eletronic mixing slows the data rate to a pace that the supercomputer can handle.

These tiny mixers were designed by our Central Development Laboratory then built and tested at the University of Virginia’s Microfabrication Laboratory.

Standing on the Great Big Thing

Years ago, staff were permitted to walk out on to the 2.3 acre surface of the Green Bank Telescope. Now, with new scientific needs requiring the GBT’s surface to be hyperaccurate, no one is allowed on the 2004 aluminum surface panels unless they are doing critical maintenance, including painting. In this photo, the shadow of the 64-foot feed arm dwarfs the folks on the dish.

Unique Telescopes

These two enormous telescopes in Green Bank, West Virginia are unique in the world. In the foreground is the Green Bank Telescope, the world’s largest fully-steerable telescope. At 485-feet high and over 300-feet across, the GBT weighs 17 million pounds. In the background, the 140-foot (43-meter) telescope is the world’s largest polar-aligned telescope.