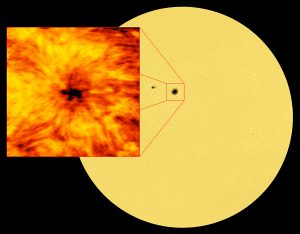

This image of the entire Sun was taken at a wavelength of 617.3 nanometers. Light at this wavelength originates from the visible solar surface, the photosphere. A cooler, darker sunspot is clearly visible in the disk, and — as a visual comparison — a depiction from ALMA at a wavelength of 1.25 millimeters is shown.

The Sun at 1.25mm

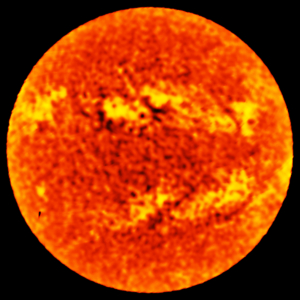

This full map of the Sun at a wavelength of 1.25 mm was taken with a single ALMA antenna using a so-called “fast-scanning” technique. The accuracy and speed of observing with a single ALMA antenna makes it possible to produce a low-resolution map of the entire solar disk in just a few minutes. Such images can be used in their own right for scientific purposes, showing the distribution of temperatures in the chromosphere, the region of the solar atmosphere that lies just above the visible surface of the Sun.

ALMA Reveals Sun in New Light

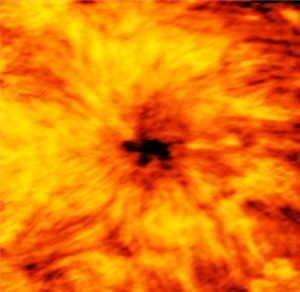

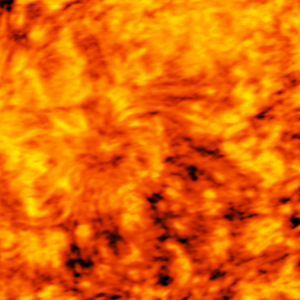

This ALMA image of an enormous sunspot was taken on 18 December 2015 with the Band 6 receiver at a wavelength of 1.25 millimeters. Sunspots are transient features that occur in regions where the Sun’s magnetic field is extremely concentrated and powerful. They are lower in temperature than their surrounding regions, which is why they appear relatively dark in visible light. The ALMA image is essentially a map of temperature differences in a layer of the Sun’s atmosphere known as the chromosphere, which lies just above the visible surface of the Sun (the photosphere). The chromosphere is considerably hotter than the photosphere. Understanding the heating and dynamics of the chromosphere are key areas of research that will be addressed by ALMA. Observations at shorter wavelengths probe deeper into the solar chromosphere than longer wavelengths. Hence, band 6 observations map a layer of the chromosphere that is closer to the visible surface of the Sun than band 3 observations.

ALMA’s Band 3 Image of the Sun

ALMA image of an enormous sunspot taken on 18 December 2015 with the Band 3 receiver at a wavelength of 3 millimeters. Sunspots are transient features that occur in regions where the Sun’s magnetic field is extremely concentrated and powerful. They are lower in temperature than their surrounding regions, which is why they appear relatively dark in visible light. The ALMA images are essentially maps of temperature differences in a layer of the Sun’s atmosphere known as the chromosphere, which lies just above the visible surface of the Sun (the photosphere). The chromosphere is considerably hotter than the photosphere. Understanding the heating and dynamics of the chromosphere are key areas of research that will be addressed by ALMA. Observations at shorter wavelengths probe deeper into the solar chromosphere than longer wavelengths. Hence, band 6 observations map a layer of the chromosphere that is closer to the visible surface of the Sun than band 3 observations.

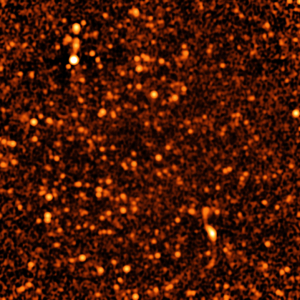

VLA Deep Field

Staring at a small patch of sky for more than 50 hours with the ultra-sensitive Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), astronomers have for the first time identified discrete sources that account for nearly all the radio waves coming from distant galaxies. They found that about 63 percent of the background radio emission comes from galaxies with gorging black holes at their cores and the remaining 37 percent comes from galaxies that are rapidly forming stars. About 2,000 discrete objects are identified in this VLA image of the distant Universe. This entire image constitutes only about one-millionth of the entire sky.

Precise Location, Distance Provide Breakthrough in Study of Fast Radio Bursts

In January 2017, for the first time, astronomers pinpointed the location in the sky of a Fast Radio Burst (FRB), allowing them to determine the distance and home galaxy of one of these mysterious pulses of radio waves. The new information rules out several suggested explanations for the source of FRBs.