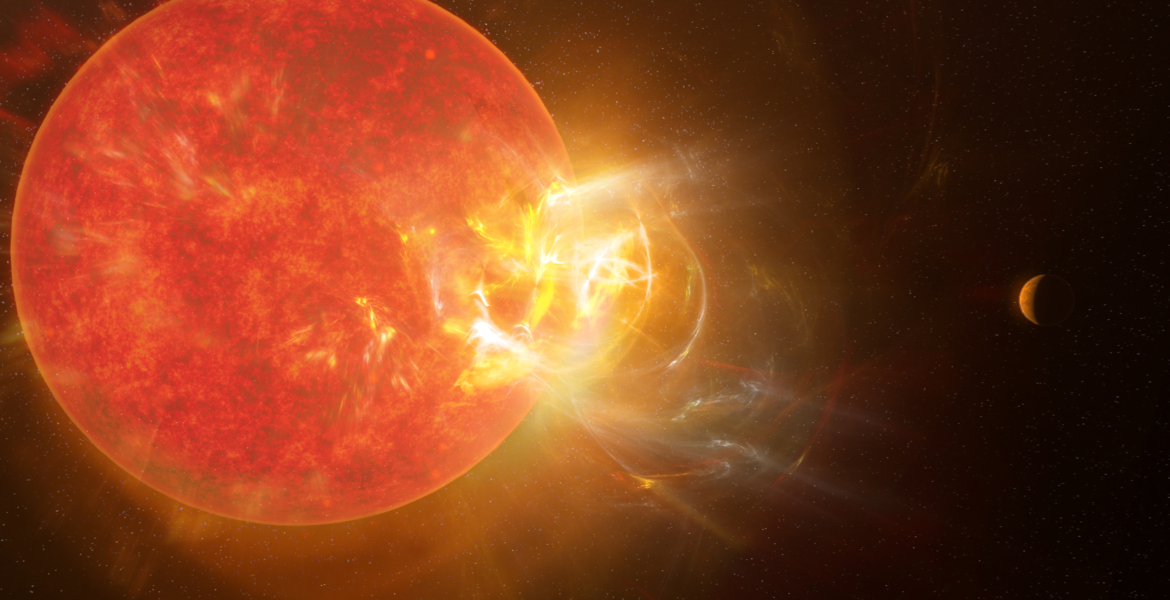

At a distance of just over four light years, Proxima Centauri is our nearest stellar neighbor and is known to be a very active M dwarf star. Its flare activity has been well known to astronomers using visible wavelengths of light, but a new study using observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) array highlight this star’s extreme activity in radio and millimeter wavelengths, offering exciting insights about the particle nature of these flares as well as potential impacts to the livability of its terrestrial, habitable-zone planets.

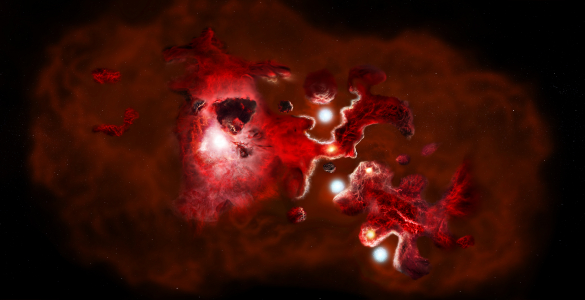

Known to host a potentially habitable planet, the star Proxima Centauri exhibits very active flare activity in optical wavelengths. Similar to flares on our Sun, these outbursts release light energy across the electromagnetic spectrum as well as bursts of particles known as stellar energetic particles. Depending on the energy and frequency of these flares, nearby planets in the habitable zone might be rendered uninhabitable as the flares strip planetary atmospheres of necessary ingredients such as ozone and water.

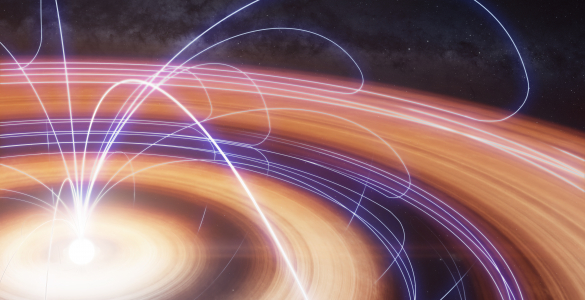

A team of astronomers, led by Kiana Burton of the University of Colorado and Meredith MacGregor of Johns Hopkins University, utilized archival data and new ALMA observations to study the millimeter-wavelength flare activity of Proxima Centauri. Proxima Centauri’s small size and strong magnetic field indicate that its entire internal structure is likely convective—unlike the Sun, which has both convective and nonconvective layers. As a result, the star is much more active. Its magnetic fields become twisted, develop tension, and eventually snap, sending streams of energy and particles outward in what astronomers observe as flares.

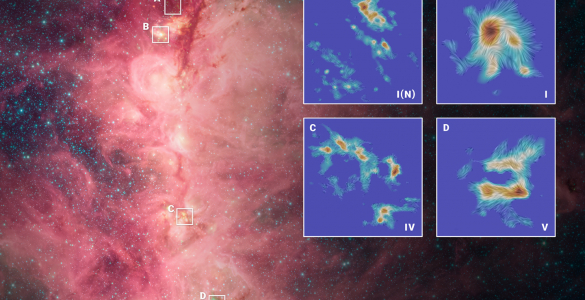

MacGregor summarized the study’s core question, “Our Sun’s activity doesn’t remove Earth’s atmosphere and instead cause beautiful auroras, because we have a thick atmosphere and a strong magnetic field to protect our planet. But Proxima Centauri’s flares are much more powerful, and we know it has rocky planets in the habitable zone. What are these flares doing to their atmospheres? Is there such a large flux of radiation and particles that the atmosphere is getting chemically modified, or perhaps completely eroded?” This research represents the first multi-wavelength study using millimeter observations to uncover a new look at the physics of flares. Combining 50 hours of ALMA observations using both the full 12-meter array as well as the 7-meter Atacama Compact Array, a total of 463 flare events were reported at energies ranging from 1024 to 1027 erg. The flares themselves were short events, ranging from 3 to 16 seconds.

“When we see the flares with ALMA, what we’re seeing is the electromagnetic radiation–the light in various wavelengths. But looking deeper, this radio wavelength flaring is also giving us a way to trace the properties of those particles and get a handle on what is being released from the star,” says MacGregor. To do so, astronomers characterize the star’s so-called flare frequency distribution in order to map out the number of flares as a function of their energy. Typically, the slope of this distribution tends to follow a power law function: smaller (less energetic) flares occur more frequently while larger, more energetic flares occur less frequently. Proxima Centauri experiences so many flares that the team detected many flares within each energy range. Furthermore, the team was able to quantify the asymmetry of the star’s highest energy flares, describing how the flares’ decay phase was much longer than the initial burst phase.

Radio- and millimeter-wavelength observations help to put constraints on the energies associated with these flares and their associated particles. MacGregor highlighted ALMA’s key role: “The millimeter flaring seems to be much more frequent–it’s a different power law than we see at the optical wavelengths. So if we only look in optical wavelengths, we’re missing critical information. ALMA is the only millimeter interferometer sensitive enough for these measurements.”

About ALMA

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of the European Southern Observatory (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) in Taiwan and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

About NRAO

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) is a facility of the U.S. National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.