Astronomers have found evidence for the most powerful magnetic field ever seen in the universe. They found it by observing a long-sought, short-lived “afterglow” of subatomic particles ejected from a magnetar — a neutron star with a magnetic field billions of times stronger than any on Earth and 100 times stronger than any other previously known in the Universe. The afterglow is believed to be the aftermath of a massive starquake on the neutron star’s surface. “And where there’s smoke, there’s fire, and we’ve seen the ‘smoke’ that tells us there’s a magnetar out there,” says Dale Frail, who used the National Science Foundation’s Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope to make the discovery.

“Nature has created a unique laboratory where there are magnetic fields far stronger than anything that can be created here on Earth. As a result, the study of these objects enables us to study the effects of extraordinarily intense magnetic fields on matter,” explains Dr. Morris L. Aizenman, Executive Officer in the Division of Astronomy at the National Science Foundation.

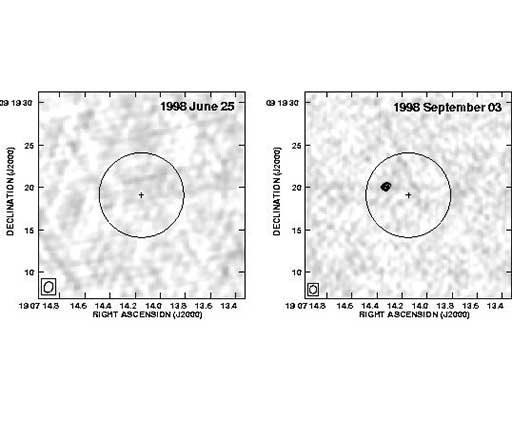

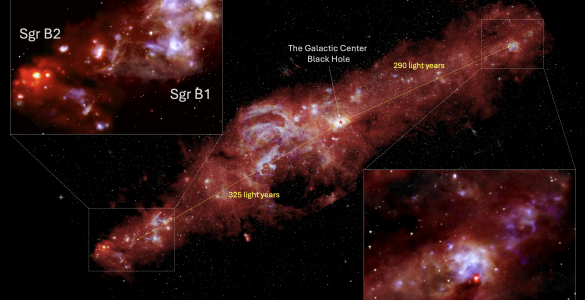

Frail, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Socorro, New Mexico, along with Shri Kulkarni and Josh Bloom, astronomers at Caltech, discovered radio emission coming from a strange object 15,000 light-years away in our own Milky Way Galaxy. The radio emission was seen after the object experienced an outburst of gamma-rays and X-rays in late August.

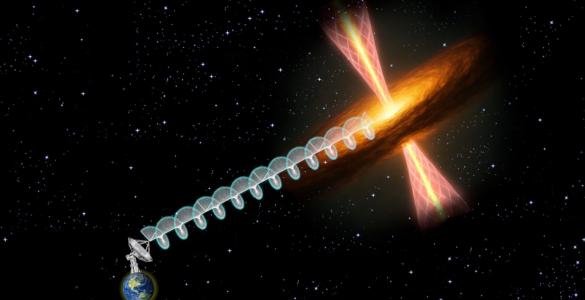

“This emission comes from particles ejected at nearly the speed of light from the surface of the neutron star interacting with the extremely powerful magnetic field,” said Kulkarni. This is the first time this phenomenon, predicted by theorists, has been seen so clearly from a suspected magnetar.

“Magnetars are expected to behave in certain ways. Astronomers have seen one type of their predicted activity previously, and now we’ve seen a completely different piece of evidence that says this is, in fact, a magnetar. That’s exciting.” Kulkarni said. The new discovery, the scientists say, will allow them to decipher further details about magnetars and their outbursts.

Magnetars were proposed in 1992 as a theoretical explanation for objects that repeatedly emit bursts of gamma-rays. These objects, called “soft gamma-ray repeaters,” or SGRs, were identified in 1986. There still are only four of these known. They are believed to be rotating, superdense neutron stars, like pulsars, but with much stronger magnetic fields.

Neutron stars are the remains of massive stars that explode as a supernova at the end of their normal lifetime. They are so dense that a thimbleful of neutron-star material would weigh 100 million tons. An ordinary pulsar emits “lighthouse beams” of radio waves that rotate with the star. When the star is oriented so that these beams sweep across the Earth, radio telescopes detect regularly-timed pulses.

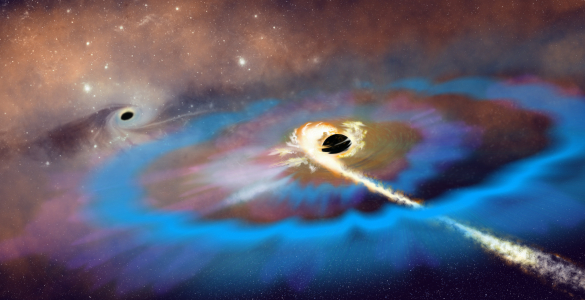

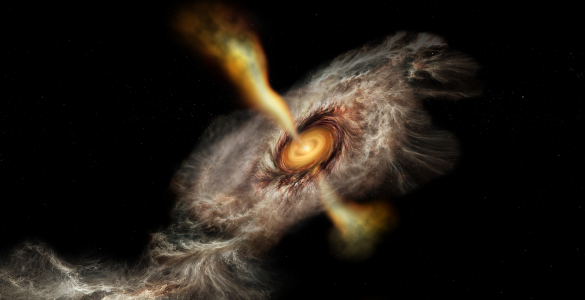

A magnetar is a neutron star with an extremely strong magnetic field, strong enough to rip atoms apart. In the units used by physicists, the strength of a magnetar’s magnetic field is about a million billion Gauss; a refrigerator magnet has a field of about 100 Gauss.

This superstrong magnetic field produces effects that distinguish magnetars from other neutron stars. First, the magnetic field is thought to act as a brake, slowing the star’s rotation. The earlier discovery of pulsations several seconds apart in three SGRs indicated rotation rates slowed just as predicted by magnetar theory.

Next, the magnetic field is predicted to cause “starquakes” in which the solid crust of the neutron star is cracked, releasing energy. That energy is released in two forms — a burst of gamma-rays and X-rays and an ejection of subatomic particles at nearly the speed of light. The gamma-ray and X-ray burst lasts no more than a few minutes, while the ejected particles, interacting with the star’s magnetic field, can produce detectable amounts of radio emission for several days.

On August 27, the SGR called 1900+14 underwent a tremendous burst, the likes of which had not been seen since 1979. “For a number of years now, I’ve been routinely looking toward the region of sky where we thought this thing might be,” said Frail, “hoping the magnetar would show itself.” It did not disappoint; on September 3, the VLA found a new source of radio emission where one had not previously existed. The source quickly faded from view one week later.

The immediate importance of this finding is that it provides a new and independent confirmation of the magnetar model. These impulsive particle “winds,” predicted by theory, carry as much energy as the flashes of hard X-ray emission and are important in slowing down the spinning magnetar.

This discovery also allows astronomers to pinpoint the exact location of the SGR to allow further study of the magnetar with other powerful telescopes. “Trying to find this source of gamma-rays was like nighttime sailing with a broken lighthouse; now, we’re no longer in the dark, and can study the magnetar for years to come,” said Bloom. In time, the free-flowing particle wind can inflate a nebula called a plerion. “This ‘windbag nebula’ can tell us a lot about the outflow of particles and the burst history of the object,” Frail said. “In fact, studying this phenomenon can give us information about the magnetar that we can’t learn any other way.”

The VLA is an instrument of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

Contact:

Dave Finley, Public Information Officer

(505) 835-7302

dfinley@nrao.edu