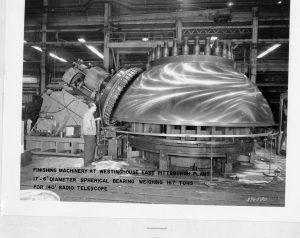

This 17.5-foot hemispherical bearing is the structural heart of the 140-foot (43-meter) telescope in Green Bank, West Virginia. It supports the full rotating weight of 2700 tons on the .005-inch thick oil film between it and the main hydrostatic pad supports. Cast by General Steel Industries it was then finished and polished by Westinghouse. Nearly 17 tons of metal were ground off during this process of getting the surface smooth with no bump more than .003 inches. The bearing still weighs in excess of 150 tons– one of the largest steel castings ever poured, certainly the largest ever cast of 3.5% nickel.

Inside the Bearing Room

The giant, shiny metal ball is the 17.5-foot hemispherical heart of the 140-foot telescope in Green Bank, West Virginia. It supports the telescope’s full rotating weight of 2700 tons on a .005-inch thick oil film (see pumps in foreground) between it and the main hydrostatic pad supports (black). The bearing is bolted to the end of the polar shaft. The shaft slowly spins against the turning of the Earth to allow the 43-meter dish telescope to keep itself aimed on a particular object in space.

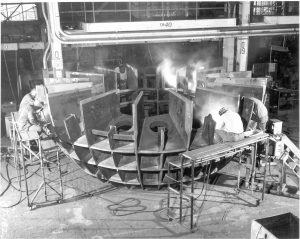

Honeycomb Hemisphere

This honeycomb of metal was to be the support structure for a 22-foot across welded steel sphere bearing for the 140-foot (43-meter) telescope in Green Bank, West Virginia. However, the welds created more than 70 small cracks in the metal, a condition known as “brittle fracture.” The cold Green Bank winters would have spelled doom for this bearing, and resulted in the loss of the entire telescope. This design was abandoned in 1962 for a smaller cast bearing.

Tricky Lift

Erection of the 266-ton dish superstructure (BUS) for the 140-foot (43-meter) telescope in Green Bank, West Virginia in November, 1964. At one point the cranes and derricks gave out, dropping the BUS to the ground. It withstood the impact without damage, and the lift continued six days later with a necessary change to the crane arrangement. After this photo was taken, the BUS was pin-wheeled to bring the declination axis shaft (the bulge at the back of the BUS) directly on its yoke arm bearings (the black C-shaped structure). In the foreground are some of the 60 surface panel sections designed and manufactured by the D. S. Kennedy Company Division of Electronic Specialties. In the background is the focal feed support on its side, ready to be erected after the panels.

Assembling the Surface

In December of 1964, work began on installing the 60 aluminum surface panels of the 140-foot (43-meter) dish telescope. At the same time, the derricks and cranes used to lift the thousands of tons of structure were being dismantled. They had been familiar sights fin Green Bank, West Virginia for over six years.

Largest Polar-Aligned Telescope

The unique 140-foot telescope in Green Bank, West Virginia. This giant telescope took six years to design and construct, and then took the astronomical world by storm in its discoveries of organic molecules in space.

A 140-foot (43-meter) aluminum-clad parabolic dish antenna sits on the world’s largest polar-aligned mount. The rounded yoke swivels around the central axis of the telescope which is aligned perfectly with the rotational axes of the Earth. In this way, the telescope can easily track objects in the sky as they appear to rise and set from the Earth’s spin on its axis.