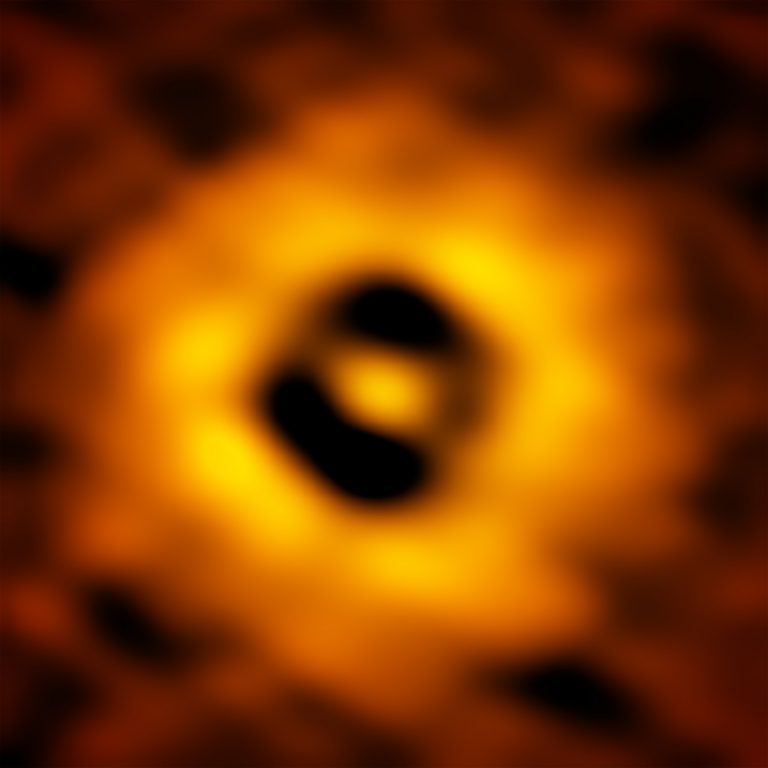

ALMA’s Best Image Yet of a Protoplanetary Disk

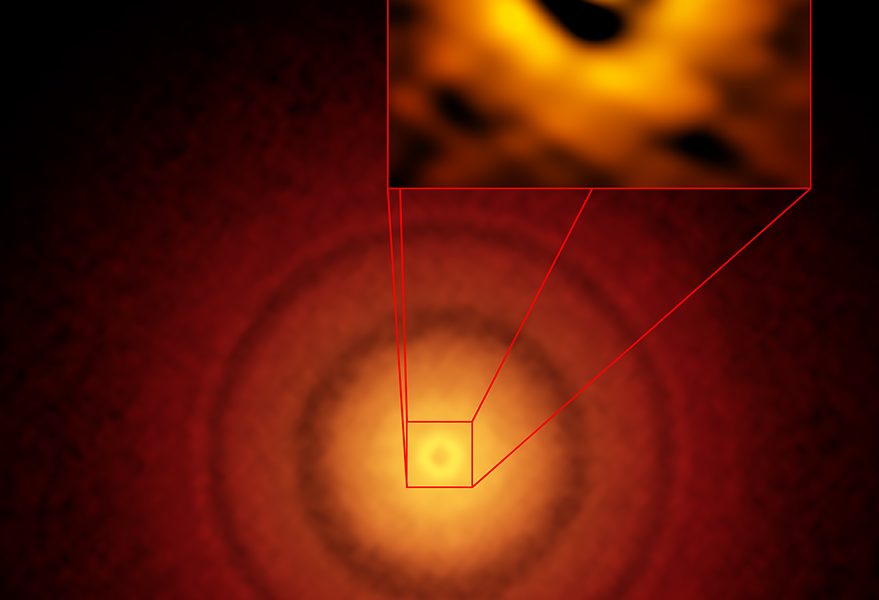

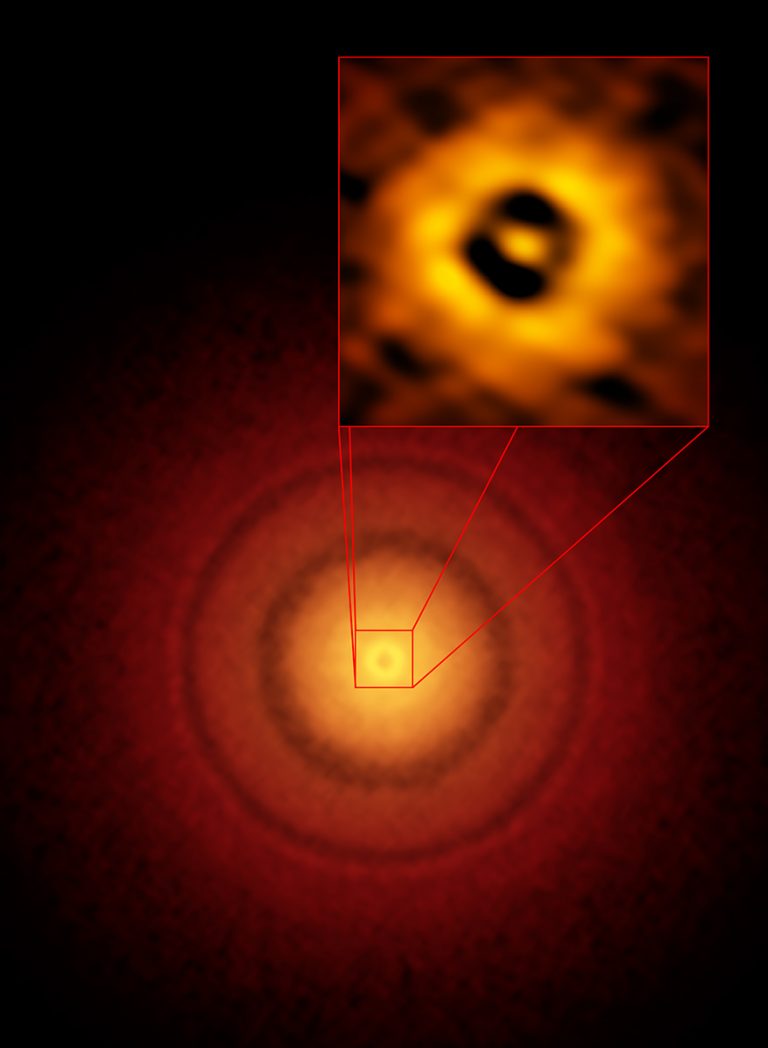

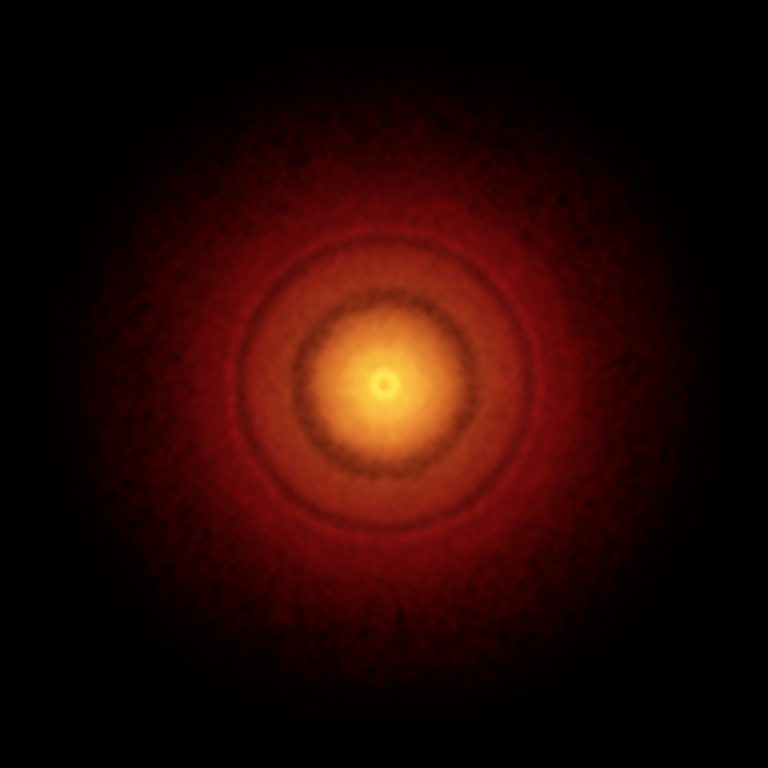

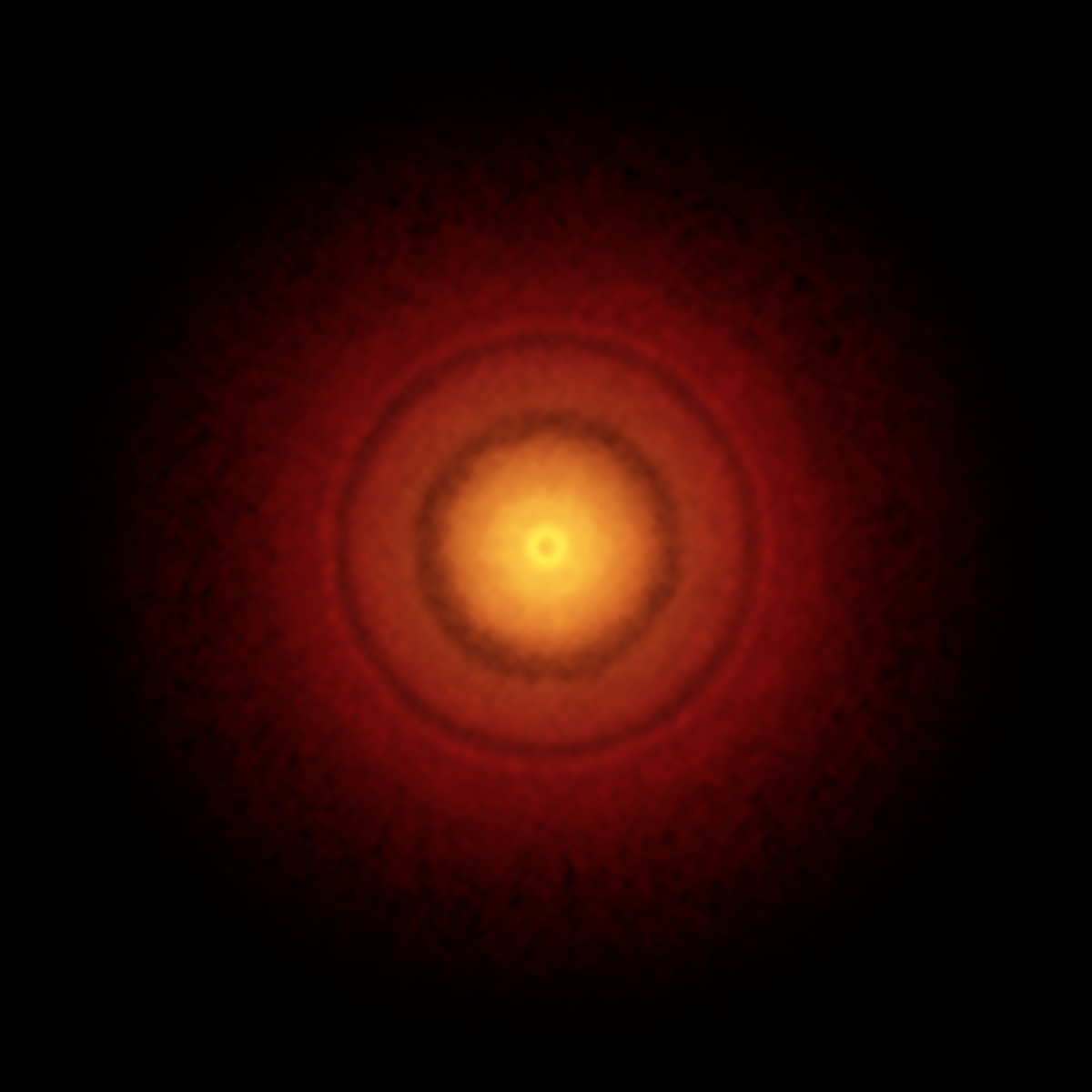

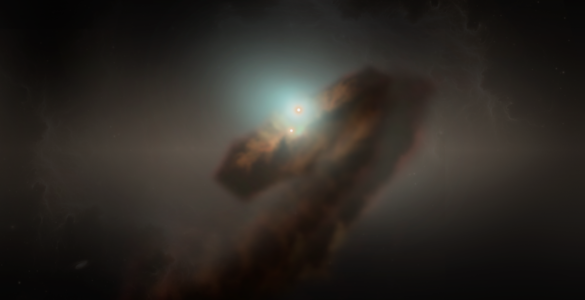

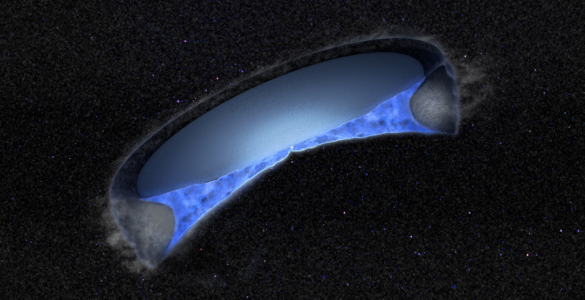

The disks of dust and gas that surround young stars are the formation sites of planets. New images from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) reveal never-before-seen details in the planet-forming disk around a nearby Sun-like star, including a tantalizing gap at the same distance from the star as the Earth is from the Sun.

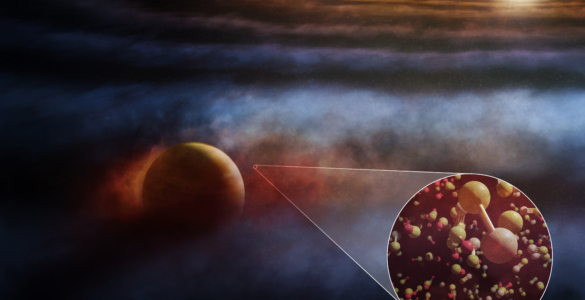

This structure may mean that an infant version of our home planet, or possibly a more massive “super-Earth,” is beginning to form there.

The star, TW Hydrae, is a popular target of study for astronomers because of its proximity to Earth (approximately 175 light-years away) and its status as a veritable newborn (about 10 million years old). It also has a face-on orientation as seen from Earth. This affords astronomers a rare, undistorted view of the complete disk.

“Previous studies with optical and radio telescopes confirm that this star hosts a prominent disk with features that strongly suggest planets are beginning to coalesce,” said Sean Andrews with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., and lead author on a paper published today in Astrophysical Journal Letters. “The new ALMA images show the disk in unprecedented detail, revealing a series of concentric dusty bright rings and dark gaps, including intriguing features that suggest a planet with an Earth-like orbit is forming there.”

Other pronounced gap features are located 3 billion and 6 billion kilometers from the central star, similar to the distances from the Sun to Uranus and Pluto in our own Solar System. They too are likely the result of particles that came together to form planets, which then swept their orbits clear of dust and gas and shepherded the remaining material into well-defined bands.

For the new TW Hydrae observations, astronomers imaged the faint radio emission from millimeter-size dust grains in the disk, revealing details on the order of one astronomical unit (about 150 million kilometers, or the distance between the Earth and the Sun). These detailed observations were made possible with ALMA’s high-resolution, long-baseline configuration. When ALMA’s dishes are at their maximum separation, up to nearly 15 kilometers apart, the telescope is able to resolve finer details. “This is the highest spatial resolution image ever of a protoplanetary disk from ALMA, and that won’t be easily beaten going forward,” said Andrews.

“TW Hydrae is quite special. It is the nearest known protoplanetary disk to Earth and it may closely resemble our Solar System when it was only 10 million years old,” said co-author David Wilner, also with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Earlier ALMA observations of another system, HL Tau, show that even younger protoplanetary disks – a mere one million years old – can display similar signatures of planet formation. By studying the older TW Hydrae disk, astronomers hope to better understand the evolution of our own planet and the prospects for similar systems throughout the Galaxy.

The astronomers’ next phase of research is to investigate how common these kinds of features are in disks around other young stars and how they might change with time or environment.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

# # #

Contact:

Charles Blue, NRAO Public Information Officer

(434) 296-0314; cblue@nrao.edu

Reference:

“Ringed Substructure and a Gap at 1 AU in the Nearest Protoplanetary Disk,” S.M. Andrews et al., 2016, appears in the Astrophysical Journal Letters [http://apjl.aas.org].

The team is composed of Sean M. Andrews (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), David J. Wilner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA) , Zhaohuan Zhu (Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA), Tilman Birnstiel (Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Heidelberg, Germany), John M. Carpenter (Joint ALMA Observatory, Santiago, Chile), Laura M. Pérez (Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Bonn, Germany), Xue-Ning Bai (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), Karin I. Öberg (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), A. Meredith Hughes (Wesleyan University, Van Vleck Observatory, Middletown, USA), Andrea Isella (Rice University, Houston, Texas, USA) and Luca Ricci (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA).

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC) and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.