Topics in This Issue:

On April 5, 2017, a team of astronomers, engineers, and technicians attempted something unprecedented; they linked together a worldwide network of radio telescopes -- including the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), with the goal of imaging the outer edges of a supermassive black hole.

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) is a worldwide network of radio astronomy facilities linked together with the goal of studying one of the most exciting objects in the known universe -- the edge of a black hole.

Supermassive black holes lurk at the center of all galaxies and contain millions or even billions of times the mass of our Sun.

The light-bending power of black holes also presents a unique opportunity to observe the so-called “shadow” of a black hole.

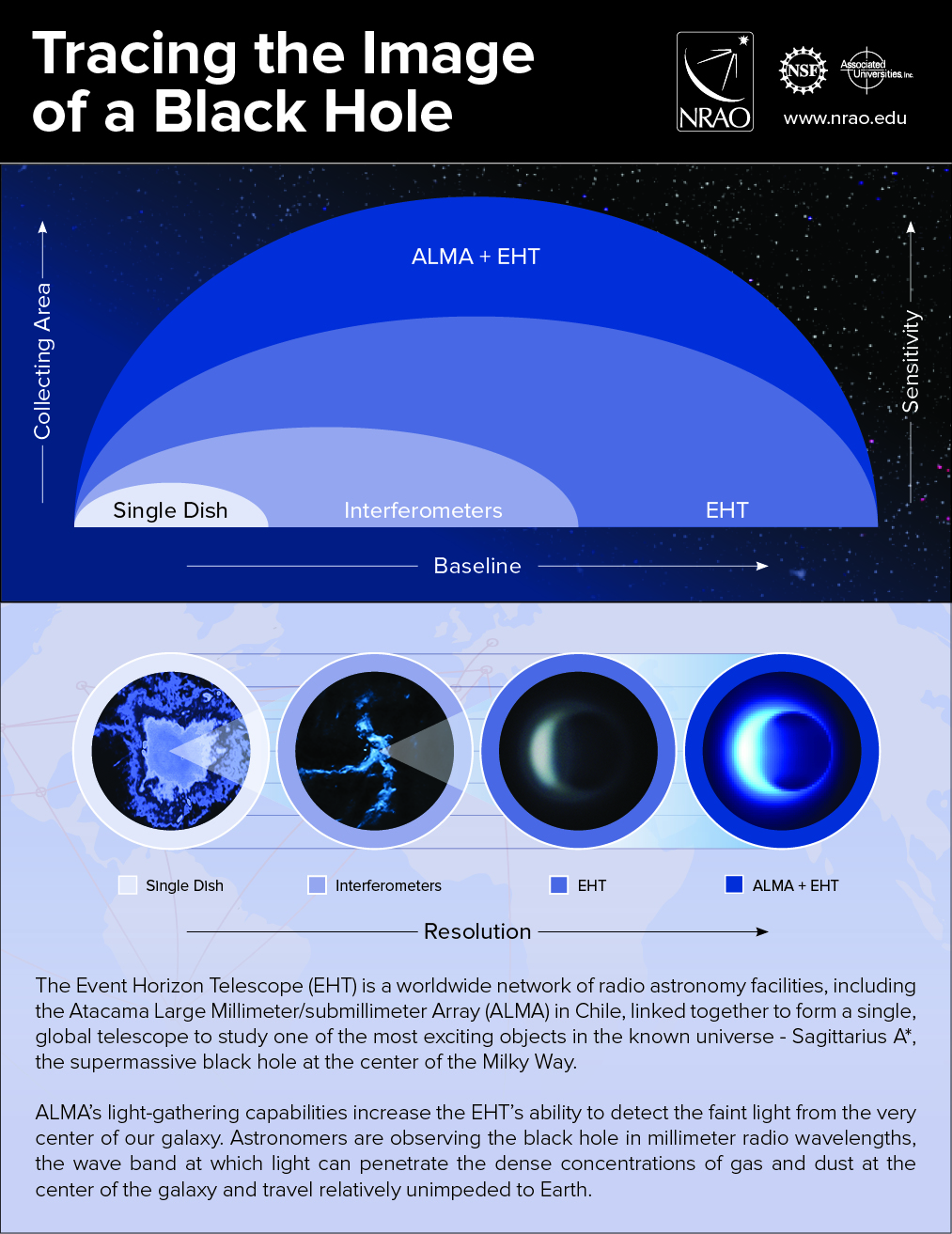

Taking a picture of the event horizon surrounding a supermassive black hole requires both resolution -- seeing fine details -- and sensitivity -- teasing out actual data from a very weak signal. But the ALMA-enabled EHT can do both!

ALMA was designed to work as an interferometer -- but that type of telescope is incompatible with the EHT. Recently, astronomers upgraded ALMA so it could become a phased array.

1. Imaging the Black Hole at the Center of Our Galaxy

On April 5, 2017, a team of astronomers, engineers, and technicians will attempt something unprecedented; they will link together a worldwide network of radio telescopes — including the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), with the goal of imaging the outer edges of a supermassive black hole.

Black holes are reality-bending concentrations of matter in space. They can be forged when star at least five times the mass of our Sun dies a spectacular death in a supernova explosion. The collapsing core from this explosion becomes so dense its gravity prevents even the fleeting particles of light from escaping its grasp.

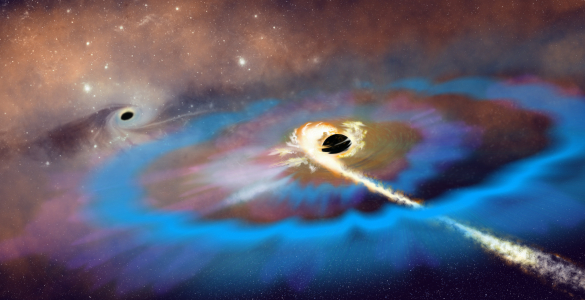

Other black holes, millions to billions of times more massive than our Sun, reside at the centers of galaxies. These supermassive black holes exert tremendous influence on their home galaxies, especially when they gorge on gas and stars.

Though astronomers have long studied the impact of black holes on the universe, no one has ever imaged the actual point of no return, where matter and energy cannot escape a black hole — the so-called event horizon.

By combining the collecting area of ALMA and other millimeter-wavelength telescopes scattered across the globe, the EHT may finally achieve that goal.

To learn more about radio telescopes, arrays, and the key to the EHT — Very Long Baseline Interferometry — read here.

Additional details are on the Joint ALMA Observatory website and the ESO website.

2. What Is the Event Horizon Telescope?

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) is a worldwide network of radio astronomy facilities linked together with the goal of studying one of the most exciting objects in the known universe — the edge of a black hole.

The EHT derives its extreme magnifying power by connecting widely spaced radio dishes across the globe into an Earth-sized virtual telescope. This technique, called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), is the same process that enables telescopes like the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to achieve such amazing power and resolution. The difference between existing VLBI facilities and the EHT is the sheer geographical scope of the EHT project, its extension to the shortest observing wavelengths, and addition of the unprecedented collecting area enabled by ALMA.

The EHT will observe the center of our galaxy at a wavelength of 1.3 millimeters. This particular wavelength is essential to peer into the otherwise obscuring veil of dust and gas near the center of our galaxy. The telescope will achieve an astounding resolution of 10 – 20 microarcseconds — which is the equivalent of reading the date on a coin in Los Angeles from the distance of New York City.

3. Black Holes and the Event Horizon

Supermassive black holes lurk at the center of all galaxies and contain millions or even billions of times the mass of our Sun. These space-bending behemoths are so massive that nothing, not even light, can escape their gravitational influence. Understanding how a black hole devours matter, powers jets of particles and energy, and distorts space and time are leading challenges in astronomy and physics.

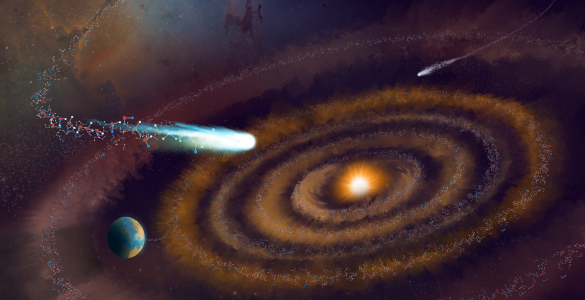

The black hole at the center of the Milky Way is a 4 million solar mass giant located approximately 26,000 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius. It is shrouded from optical telescopes by dense clouds of dust and gas, which is why observatories like ALMA, which operate at the longer millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths, are essential to study its properties.

Supermassive black holes can be relatively tranquil or they can flare up and drive incredibly powerful jets of subatomic particles deep into intergalactic space; quasars seen in the very early Universe are an extreme example. The fuel for these jets comes from in-falling material, which becomes superheated as it spirals inward. Astronomers hope to capture our Galaxy’s central black hole in the process of actively feeding to better understand how black holes affect the evolution of our Universe and how they shape the development of stars and galaxies.

High resolution imaging of the event horizon also could improve our understanding of how the highly ordered Universe as described by Einstein meshes with the messy and chaotic cosmos of quantum mechanics – two systems for describing the physical world that are woefully incompatible on the smallest of scales.

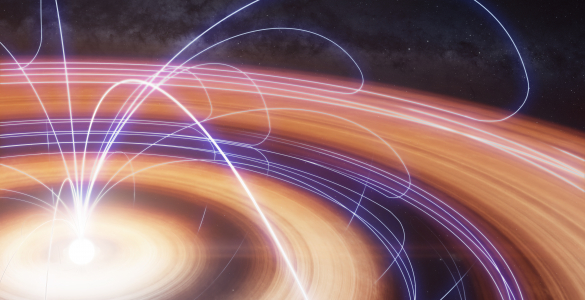

4. Shadowy Science -- A Major Science Goal for the ALMA-enabled EHT

The light-bending power of black holes also presents a unique opportunity to observe the so-called “shadow” of a black hole. Light near the event horizon of a black hole does not travel in a straight line, but instead takes on weird hyperbolic trajectories and can even achieve a stable orbit. Some of this light, which begins its journey traveling away from observers on Earth, can get twisted back around, warping in such a way that it takes a 180 degree turn. This would allow scientists to study the far-side of a black hole and actually see its shadow in space. Since the size and shape of this shadow depends on the mass and spin of black hole, these observations could tell us much about how space and time are warped in this extreme environment.

Calculations indicate a resolution of 50 micro-arcseconds (approximately 2,000 times finer than the Hubble Space Telescope) is needed to image the shadow effect. That’s equivalent to reading the date on a quarter at the distance from New York to Los Angeles. This amazing high-resolution imaging is within the reach of the ALMA-enabled Event Horizon Telescope.

5. Challenges in Obtaining an Image of a Supermassive Black Hole

Obtaining an image of a black hole is not as easy as snapping a photo with an ordinary camera. The supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, called Sagittarius A*, has a mass of approximately four million times that of the Sun, but it only looks like a tiny dot from Earth, 26 000 light-years away. To capture its image, amazingly high resolution is needed.

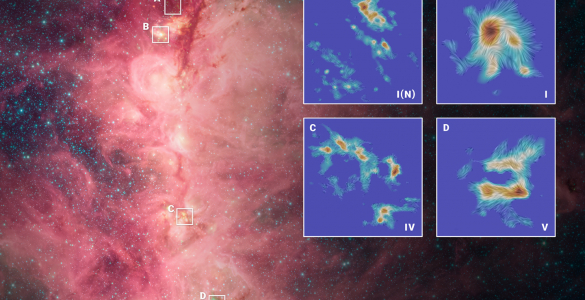

By combining the data collected by antennas thousands of kilometers apart, VLBI achieves a resolution equivalent to a radio telescope several thousands of kilometers in diameter. However, VLBI also has a lot of large blank areas that are not covered by any of the antennas. These missing parts make it difficult for VLBI to reproduce a high-fidelity image of a target object from the synthesized data. This is a common problem for all radio interferometers, including ALMA, but it can be more serious in VLBI where the antennas are located very far apart.

It might be natural to think that a higher resolution means a higher image quality, as is the case with an ordinary digital camera, but in radio observations the resolution and image quality are quite different things. The resolution of a telescope determines how close two objects can be to each other and yet still be resolved as separate objects, while the image quality defines the fidelity in reproducing the image of the structure of the observed object. For example, imagine a leaf, which has a variety of veins. The resolution is the ability to see thinner vein patterns, while the image quality is the ability to capture the overall spread of the leaf. In normal human experience, it would seem bizarre if you could see the very thin veins of a leaf but couldn’t grasp a complete view of the leaf — but such things happen in VLBI, since some portions of data are inevitably missing.

Researchers have been studying data processing methods to improve image quality for almost as long as the history of the radio interferometer itself, so there are some established methods that are already widely used, while others are still in an experimental phase. In the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) and the Global mm-VLBI Array (GMVA) projects, which are both aiming to capture the shadow of a black hole’s event horizon for the first time, researchers began to develop effective image analysis methods using simulation data well before the start of the observations.

The observations with the EHT and the GMVA were completed in April 2017. The data collected by the antennas around the world has been sent to the United States and Germany, where data processing will be conducted with dedicated data-processing computers called correlators. The data from the South Pole Telescope, one of the participating telescopes in the EHT, will arrive at the end of 2017, and then data calibration and data synthesis will begin in order to produce an image, if possible. This process might take several months to achieve the goal of obtaining the first image of a black hole, which is eagerly awaited by black hole researchers and the general astronomical community worldwide.

This lengthy time span between observations and results is normal in astronomy, as the reduction and analysis of the data is a careful, time-consuming process. Right now, all we can do is wait patiently for success to come — for a long-held dream of astronomers to be transformed into a reality.

6. Upgrading ALMA to be Part of the EHT

ALMA was designed to work as an interferometer – a telescope made up of many individual elements. Each antenna pair creates a single baseline. ALMA can produce as many as 1,291 baselines, some up to 16 kilometers long.

But before ALMA could join the Event Horizon Telescope network, it first had to transform into a different kind of instrument known as a phased array. This new version of ALMA allows its 66 antennas to function as a single radio dish 85 meters in diameter. It’s this unified power coupled with ultraprecise timekeeping that allows ALMA to link with other observatories.

A major milestone along this path was achieved in 2014 when the science team performed what could be considered a “heart transplant” on the telescope by installing a custom-built atomic clock powered by a hydrogen maser. This new timepiece uses a process similar to a laser to amplify a single pure tone, cycles of which are counted to produce a highly accurate ‘tick’.

Shep Doeleman, the principal investigator of the ALMA Phasing Project, participated during the maser installation via remote video link. “ALMA will use the ultraprecise ticking of this new atomic clock to join the aptly named Event Horizon Telescope as the most sensitive participating site, increasing sensitivity by a factor of 10,” he said.

To add the signals from all the antennas, specialized electronics and computer equipment were built at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Central Development Lab in Charlottesville, Virginia. These new circuit boards were installed into ALMA’s correlator, the supercomputer that combines the signals from the antennas.

During the upcoming observations, the signal from the phased array will be time-stamped and encoded by a dedicated atomic clock. This will allow the data to be shipped to a central processing center where it will be combined with identically timed signals from other telescopes.

The high-speed recorders that will capture the torrent of data flowing from the ALMA phased array were designed by the MIT Haystack Observatory. Software to run the new phasing system was developed by multiple institutions involved in the phasing project.

# # #

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of ESO, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC) and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

Contact: Charles Blue

434-296-0314; cblue@nrao.edu