Astronomers using the National Science Foundation’s Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) radio telescope have found an ancient black hole speeding through the Sun’s Galactic neighborhood, devouring a small companion star as the pair travels in an eccentric orbit looping to the outer reaches of our Milky Way Galaxy. The scientists believe the black hole is the remnant of a massive star that lived out its brief life billions of years ago and later was gravitationally kicked from its home star cluster to wander the Galaxy with its companion.

“This discovery is the first step toward filling in a missing chapter in the history of our Galaxy,” said Felix Mirabel, an astrophysicist at the Institute for Astronomy and Space Physics of Argentina and French Atomic Energy Commission. “We believe that hundreds of thousands of very massive stars formed early in the history of our Galaxy, but this is the first black hole remnant of one of those huge primeval stars that we’ve found.”

“This also is the first time that a black hole’s motion through space has been measured,” Mirabel added. A black hole is a dense concentration of mass with a gravitational pull so strong that not even light can escape it. The research is reported in the Sept. 13 issue of the scientific journal Nature.

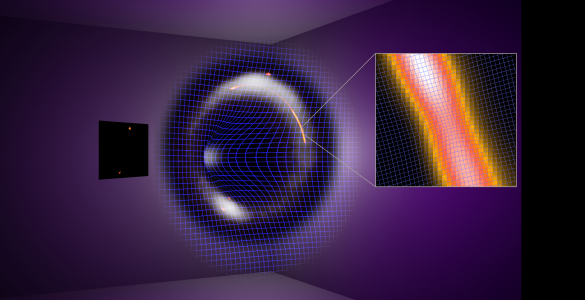

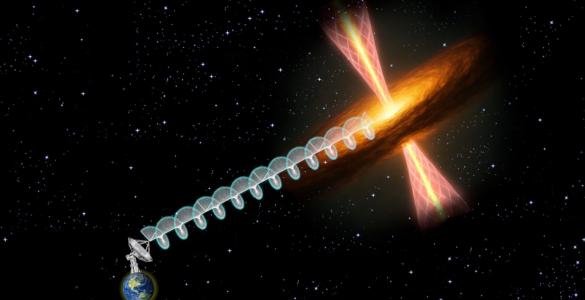

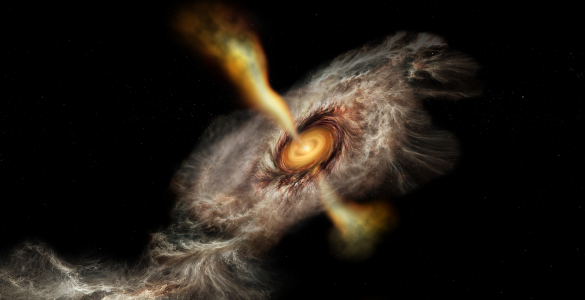

The object is called XTE J1118+480 and was discovered by the Rossi X-Ray satellite on March 29, 2000. Later observations with optical and radio telescopes showed that it is about 6,000 light-years from Earth and that it is a in which material sucked by the black hole from its companion star forms a hot, spinning disk that spits out “jets” of subatomic particles that emit radio waves.

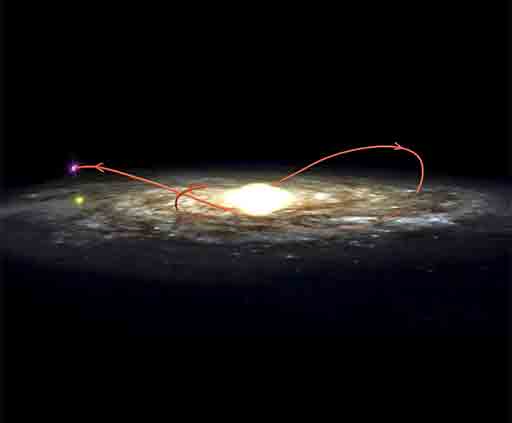

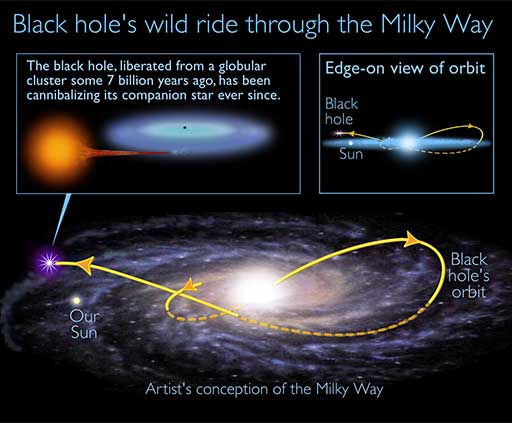

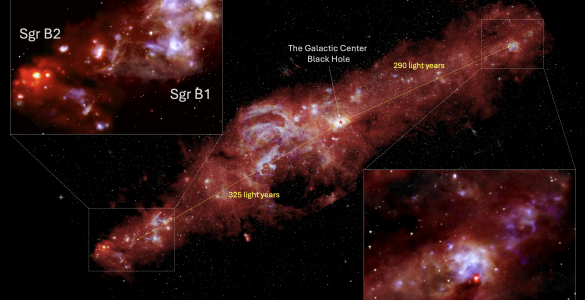

Most of the stars in our Milky Way Galaxy are within a thin disk, called the plane of the Galaxy. However, there also are globular clusters, each containing hundreds of thousands of the oldest stars in the Galaxy which orbit the Galaxy’s center in paths that take them far from the Galaxy’s plane. XTE J1118+480 orbits the Galaxy’s center in a path similar to those of the globular clusters, moving at 145 kilometers per second (90 miles per second) relative to the Earth.

How did it get into such an orbit? “There are two possibilities: either it formed in the Galaxy’s plane and was somehow kicked out of the plane or it formed in a globular cluster and was kicked out of the cluster,” said Vivek Dhawan, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Socorro, New Mexico.

A massive star ends its life by exploding as a supernova, leaving either a neutron star or a black hole as a remnant. Some neutron stars show rapid motion, thought to result from a sideways “kick” during the supernova explosion. “This black hole has much more mass — about seven times the mass of our Sun — than any neutron star,” said Dhawan. “To accelerate it to its present speed would require a kick from the supernova that we consider improbable,” Dhawan added.

“We think it’s more likely that it was gravitationally ejected from the globular cluster,” Dhawan said. Simulations of the gravitational interactions in globular clusters have shown that the black holes resulting from the collapse of the most massive stars should eventually be ejected from the cluster.

“The star that preceded this black hole probably formed in a globular cluster even before our Galaxy’s disk was formed,” Mirabel said. “What we’re doing here is the astronomical equivalent of archaeology, seeing traces of the intense burst of star formation that took place during an early stage of our Galaxy’s development.”

The black hole has consumed so much of its companion star that the inner layers of the smaller star — only about one-third the mass of the Sun — now are exposed. The scientists believe the black hole captured the companion before being ejected from the globular cluster, as if it were grabbing a snack for the road.

“Because this microquasar happened to be relatively close to the Earth, we were able to track its motion with the VLBA even though it’s normally faint,” said Mirabel. “Now, we want to find more of these ancient black holes. There must be hundreds of thousands swirling around in our Galaxy.”

The astronomers used the VLBA to observe XTE J1118+480 in May and July of 2000, using the VLBA’s great resolving power, or ability to see fine detail, to precisely measure the object’s movement against the backdrop of more-distant celestial bodies. The VLBA observations were made at radio frequencies of 8.4 and 15.4 GHz.

In addition, they found that the object appears in optical images made for the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS) taken 43 years apart. The POSS images were digitized to allow for rapid search and analysis by the Space Telescope Science Institute. The data from both the radio and optical images allowed the astronomers to calculate the object’s orbital path around the Galactic center.

“With the VLBA, we could start observing soon after this object was discovered and get extremely precise information on its position. Then, we were able to use the digitized data from the Palomar surveys to extend backward the time span of our information. This is a great example of applying multiple tools of modern astronomy — telescopes covering different wavelengths and digital databases — to a single problem,” said Dhawan.

In addition to Mirabel and Dhawan, the research was performed by Roberto Mignani of the European Southern Observatory; Irapuan Rodrigues, who is a fellow of the Brazilian National Research Council at the French Atomic Energy Commission; and Fabrizia Guglielmetti of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, MD.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

Contacts:

Dave Finley, National Radio Astronomy Observatory

(505) 835-7302

dfinley@nrao.edu

Ray Villard, Space Telescope Science Institute

(410) 338-4514

villard@stsci.edu