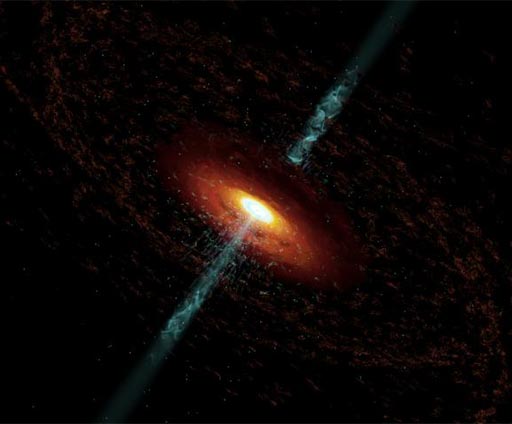

Scientists have caught a supermassive black hole in a distant galaxy in the act of spurting energy into a jet of electrons and magnetic fields four distinct times in the past three years, a celestial take on a Yellowstone geyser.

This quasar-like “active” galaxy is essentially a scaled-up model of the so-called microquasars within our Milky Way Galaxy, which are smaller black holes with as much as ten times the mass of the sun. This means that scientists can now use their close-up view of microquasars to develop working models of the most massive and powerful black holes in the universe.

These results — published in the June 6 issue of Nature — are the fruit of a three-year monitoring campaign with the National Science Foundation’s Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), a continent-wide radio-telescope system, and NASA’s Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer.

“This is the first direct, observational evidence of what we had suspected: The jets in active galaxies are powered by disks of hot gas orbiting around supermassive black holes,” said Alan Marscher of the Institute for Astrophysical Research at Boston University, who led this international team of astronomers.

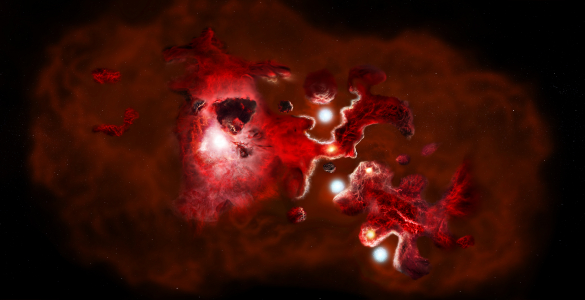

Active galaxies are distant celestial objects with exceedingly bright cores, often radiating with the brilliance of thousands of ordinary galaxies, fueled by the gravity of a central million- to billion-solar-mass black hole pulling in copious amounts of interstellar gas.

Marscher and his colleagues have established the first direct observational link between a supermassive black hole and its jet. The source is an active galaxy named 3C120 about 450 million light-years from Earth. This link has been observed in microquasars, several of which are scattered across the Milky Way Galaxy, but never before in active galaxies, because the scale (distance and time) is so much greater.

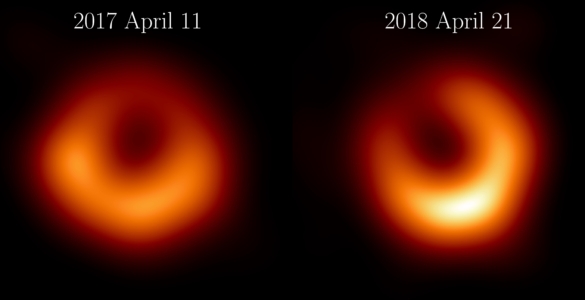

The jets in galaxy 3C120 are streams of particles shooting away perpendicularly from the plane of a black hole’s accretion disk, moving at 98 percent of the speed of light. In microquasars, radio-emitting features become visible in a jet shortly after X rays from the accretion disk get dimmer — as if the accretion disk suddenly flushes into the black hole and disappears, fueling the jet. These radio “blobs” then appear to move at faster-than- light speeds, an illusion caused by their ultra-high speeds and their orientation with respect to Earth.

Now the team of scientists sees this same phenomenon in 3C120. Roughly every ten months, the X-ray-emitting accretion disk around its supermassive black hole becomes suddenly dim, and a month later the telltale bright spot of radio emission appears in the jet. Over a three-year period, the team observed a series of radio blobs floating along the particle jet like smoke puffs, each time following a dip in the brightness of X rays from the accretion disk.

“What we are likely seeing is the inner part of the accretion disk becoming unstable and suddenly plunging into the black hole,” said Marscher. “We detect a ‘dip’ in the X-ray flux as the hot gas in the disk disappears after it passes the event horizon. The remainder of the disk is channeled into the jets, which we see as a knot of radio emission bubbling away from the black hole. Slowly the accretion disk fills with more interstellar gas until about ten months later, when something disturbs the accretion disk orbit, and the whole thing flushes and blows again.”

Joining Marscher on this observation and analysis are Svetlana Jorstad of Boston University; Jose-Luis Gomez of the Astrophysical Institute of Andalucia in Granada, Spain; Margo Aller of the University of Michigan; Harri Terasranta of the Helsinki University of Technology; Matthew Lister of NRAO; and Alastair Stirling of the University of Central Lancashire, England.

The VLBA is a continent-wide radio-telescope system, with one telescope on Hawaii, another on St. Croix in the Caribbean, and eight others in the continental United States. Part of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, the VLBA offers the highest resolving power, or ability to see fine detail, of any telescope available. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

The Rossi Explorer was launched by NASA in 1995 to study black holes, neutron stars and pulsars. The Rossi Explorer is operated by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

The research on 3C120 was supported by funding from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation.

Contact:

Dave Finley, Public Information Officer

Socorro, NM

(505) 835-7302

dfinley@nrao.edu