The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) has detected the most distant clouds of star-forming gas yet found in normal galaxies in the early Universe. The new observations allow astronomers to explore how the first galaxies built up and how they cleared the cosmic fog during the era of reionization. This is the first time that such galaxies are seen as more than just faint blobs.

When the first galaxies started to form a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, the Universe was full of a fog of hydrogen gas. But as more and more brilliant sources — both stars and quasars powered by huge black holes — started to shine they cleared away the mist and made the Universe transparent to ultraviolet light [1]. Astronomers call this the epoch of reionization, but little is known about these first galaxies, and up to now they have just been seen as very faint blobs. But now new observations using the power of ALMA are starting to change this.

A team of astronomers led by Roberto Maiolino (Cavendish Laboratory and Kavli Institute for Cosmology, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom) trained ALMA on galaxies that were known to be seen only about 800 million years after the Big Bang [2]. The astronomers were not looking for the light from stars, but instead for the faint glow of ionized carbon [3]coming from the clouds of gas from which the stars were forming. They wanted to study the interaction between a young generation of stars and the cold clumps that were assembling into these first galaxies.

Neither were the astronomers looking for the extremely brilliant rare objects — such as quasars and galaxies with very high rates of star formation — that had been seen up to now. Instead they concentrated on rather less dramatic, but much more common, galaxies that reionized the Universe and went on to turn into the bulk of the galaxies that we see around us now.

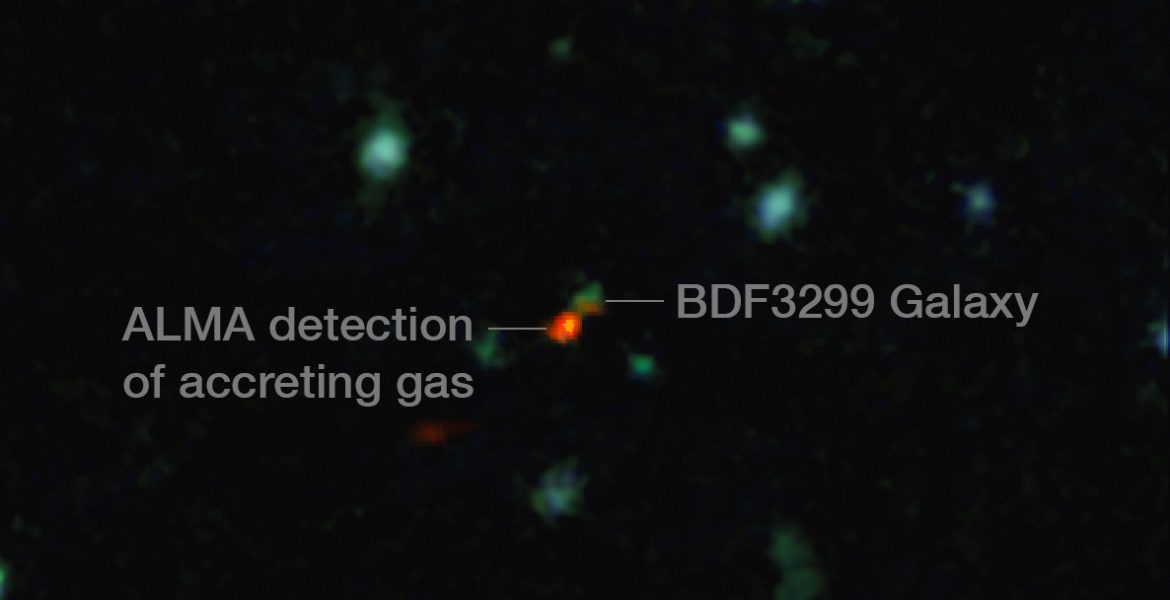

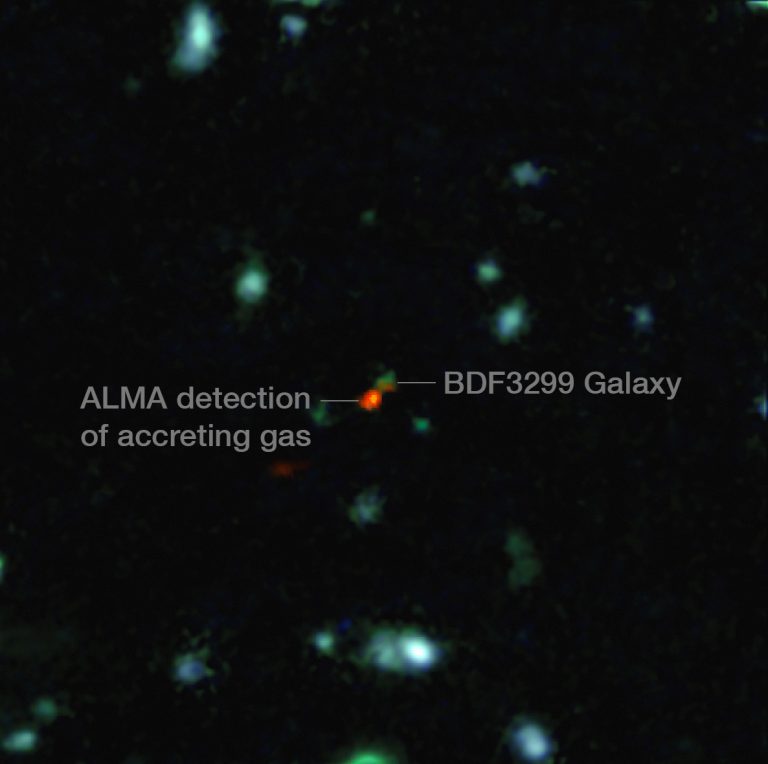

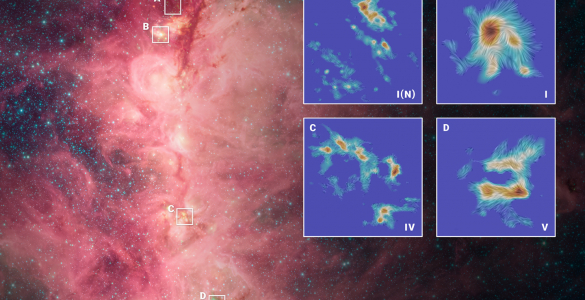

From one of the galaxies — given the label BDF2399 — ALMA could pick up a faint but clear signal from the glowing carbon. However, this glow wasn’t coming from the center of the galaxy, but rather from one side.

Co-author Andrea Ferrara (Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, Italy) explains the significance of the new findings: “This is the most distant detection ever of this kind of emission from a ‘normal’ galaxy, seen less than one billion years after the Big Bang. It gives us the opportunity to watch the build-up of the first galaxies. For the first time we are seeing early galaxies not merely as tiny blobs, but as objects with internal structure!”

The astronomers think that the off-center location of the glow is because the central clouds are being disrupted by the harsh environment created by the newly formed stars — both their intense radiation and the effects of supernova explosions — while the carbon glow is tracing fresh cold gas that is being accreted from the intergalactic medium.

By combining the new ALMA observations with computer simulations, it has been possible to understand in detail key processes occurring within the first galaxies. The effects of the radiation from stars, the survival of molecular clouds, the escape of ionizing radiation and the complex structure of the interstellar medium can now be calculated and compared with observation. BDF2399 is likely to be a typical example of the galaxies responsible for reionization.

“We have been trying to understand the interstellar medium and the formation of the reionization sources for many years. Finally to be able to test predictions and hypotheses on real data from ALMA is an exciting moment and opens up a new set of questions. This type of observation will clarify many of the thorny problems we have with the formation of the first stars and galaxies in the Universe,” adds Ferrara.

Maiolino concludes: “This study would have simply been impossible without ALMA, as no other instrument could reach the sensitivity and spatial resolution required. Although this is one of the deepest ALMA observations so far it is still far from achieving its ultimate capabilities. In future ALMA will image the fine structure of primordial galaxies and trace in detail the build-up of the very first galaxies.”

# # #

Contact: Charles Blue

cblue@nrao.edu; (434) 296-0314

Notes

[1] Neutral hydrogen gas very efficiently absorbs all the high-energy ultraviolet light emitted by young hot stars. Consequently, these stars are almost impossible to observe in the early Universe. At the same time, the absorbed ultraviolet light ionizes the hydrogen, making it fully transparent. The hot stars are therefore carving transparent bubbles in the gas. Once all these bubbles merge to fill all of space, reionization is complete and the Universe becomes transparent.

[2] They had redshifts ranging from 6.8 to 7.1.

[3] Astronomers are particularly interested in ionized carbon as this particular spectral line carries away most of the energy injected by stars and allows astronomers to trace the cold gas out of which stars form. Specifically, the team was looking for the emission from singly ionized carbon (known as [C II]). This radiation is emitted at a wavelength of 158 micrometers, and by the time it is stretched by the expansion of the Universe arrives at ALMA at just the right wavelength for it to be detected at a wavelength of about 1.3 millimeters.