2,712 miles, 3 covid vaccines, 1000 forms, 4 Trader Joes stops later and I have photographed the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA).

The first time I crested the hill approaching the VLA, in April 2022, I felt that I had been transported, a la Jodie Foster. We all know that the VLA is the place where aliens first made contact, but I felt like I was the alien arriving on another planet. The scale of the dishes is, well, astronomical. The array spans miles of the San Augustin Plains, surrounded by low mountains in the distance. And the dishes are big. Like huge. A single dish weighs 230 tons and is 92 feet tall. Big enough to make us tiny humans feel like we would be easily dominated if they decided to come to life.

I pulled over a few miles before arriving at the site and turned my phone to airplane mode, then turned it off completely. Radio interference is no joke. Without my road trip music to accompany me, I could really contemplate where I was. The VLA is a humbling and inspiring place, and I felt extremely honored to be invited to photograph the site. It’s an incredible opportunity for an astrophotographer because the VLA is closed to the public at night. Getting access is not easy. The science being done there is extraordinarily sensitive, and the dishes astonishingly delicate, so the security is airtight.

I was greeted by a kind but suspicious guard who eventually let me enter when I name-dropped my site host, Jeff Hellerman. Another accomplished astrophotographer who would serve as my guide around the NSF-owned, top-secret government facility (just kidding, but that is kinda how it feels).

We toured around the area while we waited for the sun to set and planned the locations we wanted to shoot. This time, the dishes were in the A configuration, which means the dishes are the farthest apart from each other. This large geographic spread enables astronomers to see fine details in radio emissions. They go from A, (farthest) to D (closest), to C (a little less close), to B (even less close), and then back to A. The 230 ton dishes are moved along railroad tracks using a specialized transporter. That process is something I would love to see. A theme that kept coming up in my mind during my visits was the true power of human ingenuity and teamwork. The VLA is truly amazing.

As soon as the sun starts to really set (when it is 4 to 6 degrees below the horizon), a phenomenon called blue hour happens. It is my absolute favorite time of night to take photos. The sun has sunk far enough below the horizon that the stars appear bright, but there is still some light refracting through the atmosphere, creating a bright blue sky.

In April, Orion still shines bright early in the evening, and I was able to capture it above an antenna. I used a starglow filter to diffuse the light of the stars, making the brighter ones appear bigger so the constellations are easier to see. This method also helps highlight the color of the stars. We can see Orion’s top left (to us) shoulder is bright orange, meaning the star is nearing the end of its life. It burns less hot than the bright blue star on our left, Sirius, the dog star. The brightest star in the night sky. Actually, two stars. Sirius is a binary star, two stars orbiting one another closely. Invisible to the naked eye, but easily seen in a large telescope.

Another exciting phenomenon we witnessed that night was the zodiacal light, also known as false dawn or dusk. In the photo below, we can see an angled diffuse beam of light in the middle of the image. In order to see zodiacal light, you need to have dark skies. With light pollution in the sky, the faint zodiacal light can’t compete and is washed out.

The light comes from sunlight illuminating dust and ice along that plane, far out in the solar system. Here’s another shot showing the zodiacal light. And of course, we had to get up at 3am to capture the low arch of the Spring Milky Way. Finally, we went back to a meeting room, I threw my pad on the floor, and slept for a few hours before beginning my 6-hour drive back home. Lots of coffee was consumed.

Then came July. Prime Milky Way photography season if you ask me. The center of the Milky Way is right up and shining at you as soon as it gets dark, and it’s not freezing. Boy was I pumped to get back there. Not only that, but the dishes were going to be in the D configuration this time, super close together, and very photogenic. The compact configuration allows astronomers to observe diffuse radio emissions. Below we can see just how close they get!

Standing below the beeping and humming dishes in the darkness under the stars is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It sounds like the dishes are talking to each other in their own language. They all move together, it’s hard to not think of them as alive. We were also treated to something a lot of astrophotographers shy away from, a pretty darn full moon. But me? I like the moon. The rising moonlight is red and colorful, just like the setting and rising sun, because it has more atmosphere to refract through.

Then came September, which was probably the most exciting of all the shoots. The first thing I noticed when I pulled up to the site, besides the giant dishes, were the flowers. There were so many pretty yellow flowers everywhere. I was so excited to shoot them with the stars and the dishes. Little did I know, I would soon be distracted by something much more intense than flowers. Lightning!

As we were setting up to shoot, the clouds started rolling in. “Ohhhh no,” I thought. I drove six hours to get here to take photos of the night sky, and a sky full of clouds is not what I was hoping for. But as the clouds rolled in, so did the light. Natural light in the sky. Electrical discharges, lightning. Jeff and I were wary at first, we didn’t want to get struck. But as we continued watching we realized that the storm was behind a distant mountain range and passing by us, slowly moving away, and we were at a safe distance to keep clicking.

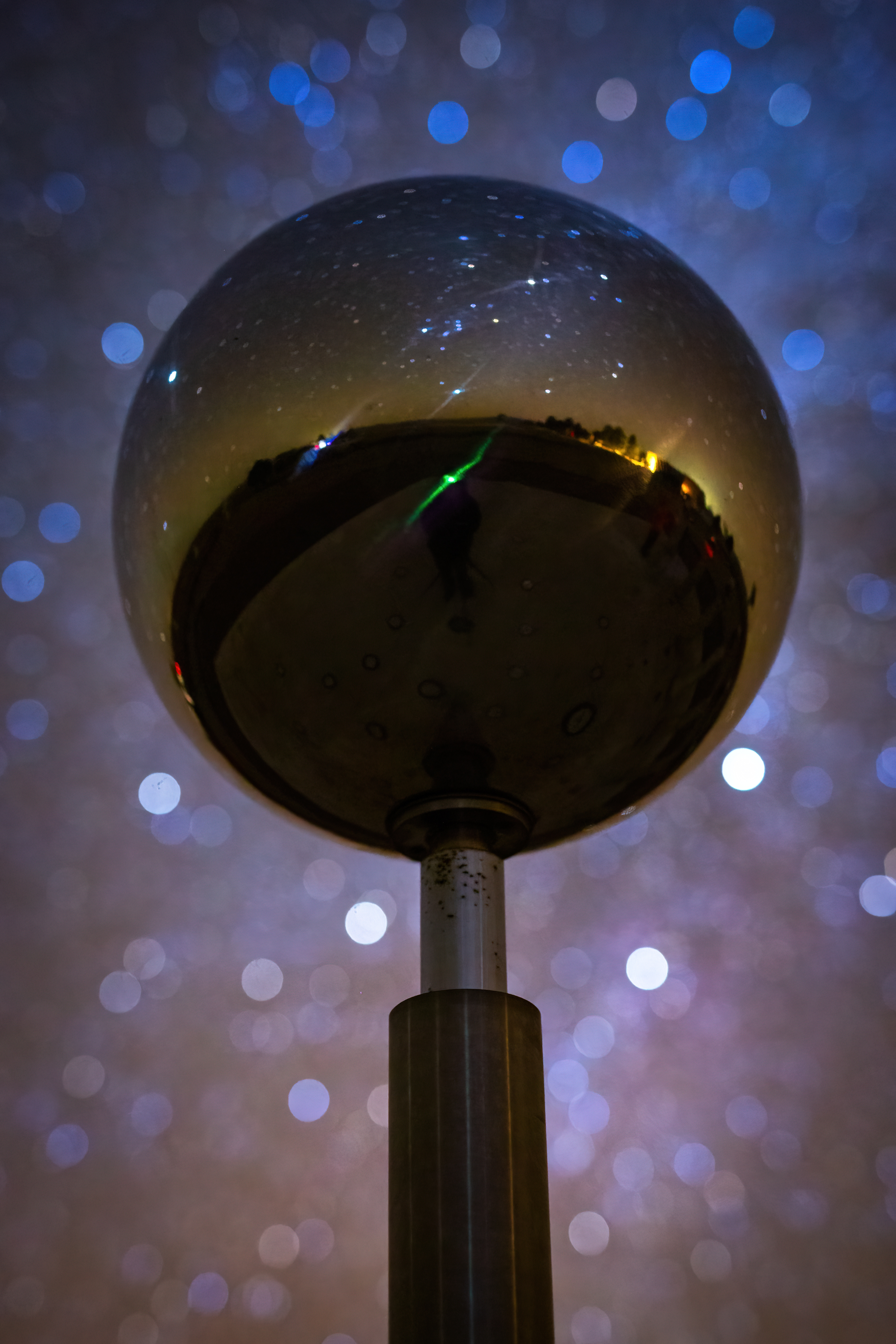

And then, just like that, the storm passed. So back to flowers. I really wanted to make the flowers shine, so I got up close and focused on them instead of the stars. This creates an effect known as bokeh, where things in the background are blurred out of focus. I love how this looks with stars, it also makes the bright constellations shine, and we can see the big dipper below.

While wandering around to get this shot, I was walking along the dirt roads that crisscross the site and happened to hear something. I knew exactly what it was when I heard it. A universal warning known to anyone who inhabits the southwestern US. Tsssssk, tsssssk, tsssssk. A rattler. I shone my light about 6 feet in front of me and saw a giant rattlesnake curled up warming its belly on the last of the desert sand heat. Thank you for the warning, I politely said, and turned right around.

The only bad thing about the perfect time of the year to shoot is that it is also the perfect time of year for my number one dreaded enemy, mosquitos. The San Agustin Plains saw record rainfalls in 2022. Above you can see the reflection of the stars in the standing water all around the dishes. And while it is super cool for reflection shots, it is also the number one breeding ground for, you guessed it, mosquitos. They can smell my fear. I left the VLA that next morning with an uncountable number of bites, many of which were on my face. Even after bathing in deet. It was worth it.

Then, my last VLA shoot. I approached the site with both sadness and elation knowing it would be my last shoot there for a while, but proud of myself for accomplishing so much over the past year. And honored that the security guards no longer looked at me with such suspicion.

It was November, so we were back to freezing again. But Jeff had come prepared with hand and foot warmers, and I wasn’t complaining, because I knew my tiny mortal enemies would be nowhere in sight.

And I also wanted to capture something that I hadn’t been able to yet, star trails. A log of the earth’s rotation as we spin around in space. We were lucky that the one dish they keep out of rotation for maintenance was out on the test pad and under the cloudless dark sky. I set up my camera to get the north star just above the dish, creating circles of starlight with a long enough exposure.

This radio-sundial was constructed from piers formerly used to support antennas in the Bracewell Radio Telescope which was built in 1952.

All in all, this has been one of the best experiences of my life. I am so thankful to all of the VLA staff for the opportunity to do what I love in one of the most beautiful and striking places on this planet. And who knows, maybe the aliens were watching us the whole time.